The daily practice of offering oneself to God’s will

February 27, 2015

In writing about charity as one of the characteristic virtues of the Priests of the Sacred Heart, Fr. Dehon equates its practice with an act of immolation. For Dehon, “immolation” is a synonym for “oblation,” which he understands as the whole-hearted self-offering that an individual makes to God on a daily basis.

With over 25 years of experience living community life, Dehon wrote the Spiritual Directory as a guide for the Priests of the Sacred Heart. He notes that human frailty, the source of “perplexities, vexations, and contradictions,” not only grounds the act of immolation in reality, but also tests its earnestness. Yet, Fr. Dehon also recognizes that charity, as an act of oblation, transforms the pains of a common life into a “union of hearts and a family spirit.”

The General Chapter of the Priests of the Sacred Heart re-wrote their Rule of Life in 1979 and took up the virtue of charity as practiced within community. While the manner of expression has changed from the time of Fr. Dehon, the spirit has remained the same, as evidenced in the following numbers [63-67] from the Rule of Life.

“Our community life is not only a means to an end: although always in need of improvement, it is the fullest realization of our Christian life. We let ourselves be permeated with the love of Christ and we hear His prayer Sint unum [“that all may be one”]: we do our utmost to make our communities authentic centers of Gospel life, particularly by openness, sharing, and hospitality, while respecting those places reserved for the community.

“Imperfect, certainly, like all Christians we want however to set up a milieu which is favorable to the spiritual progress of each one. How else to attain this, if not by deepening in the Lord even our most ordinary relationships with each of our brothers? Charity must be an active hope for what others can become with the help of our fraternal support. The mark of its genuineness will be the simple way with which all strive to understand what each one has at heart.

“Through fellowship even above and beyond conflicts, and through mutual forgiveness, we would like to be a sign that the fraternity for which people thirst is possible in Jesus Christ and we would like to be its servants.

“Community life requires that each one accept others as they are with their personalities, their duties, their initiatives and their limits, and that each one allow himself to be called into question by his brothers.

“These requirements are the basis of a true dialogue, in mutual respect, fraternal love, solidarity, and co-responsibility. In this, too, the community strives to witness to Christ, in whom it is brought together. At the same time it can lend valuable assistance toward the full development of each of its members.”

December 19, 2014

“The great work of Jesus was the Church. He founded it upon the faith of Peter and upon the authority of the apostles.” As Fr. Dehon concludes his series of meditations on the Priestly Heart of Jesus, he wants priests to appreciate how they collaborate in this great work, and through them how “it develops, it grows, it is immortal.”

“The priest will have his works,” Dehon notes and lists what most people consider priestly tasks. “He will, perhaps, build a church, an oratory, or erect an altar. He will found or introduce a Confraternity, an Association, and periodical exercises of piety.” To this list he adds what many might find surprising. “He will organize new works: Patronages, Study-clubs; groups of young men and boys; Syndicates, Mutual Aid Societies, and Cooperative Unions.”

For Fr. Dehon, who offered his entire life to promote the reign of the Heart of Jesus “in souls and societies,” there was little need to distinguish between spiritual and material needs. “These establishments will be permanent,” he writes, “and the priest will live on in his works of charity and zeal; he will survive. He will feel intense joy on the day he founds such a work.

No doubt reflecting on his own experience of establishing and running The Patronage of St. Joseph for boys and young workers, facilitating a study-club for future employers, and advocating for Cooperative Unions for factory workers, he cautions, “The period of sowing the seed may be a time of difficulty and trial, but at the end of his life the priest will have the consolation of leaving a living work fruitful in grace.

“After his death he will still speak in his works, in the good that they do. If he has founded a periodical Mission or Retreat, established a Third Order, if he has published helpful, stimulating books, favored and encouraged the Catholic Press—these works will prolong his apostolate. If he has published or circulated good books, he will be preaching even after death.”

Encouraging priests to think outside “the sacristy” and beyond sacramental ministry, Fr. Dehon exhorts, “O Priests, have the holy ambition to support the useful works founded by your predecessors, and to add new enterprises to them when necessary or helpful. You will thereby survive yourselves, you will become immortal even on earth, and your works will speak for you before God.”

In the spirit of oblation or self-offering, he concludes, “Establish your works with the zeal, the charity, the tender interest that animated the Priestly Heart of Jesus when he founded his Church.”

Fr. Leo John Dehon, SCJ, The Priestly Heart of Jesus, 32nd Meditation

December 12, 2014

“I very much want and ardently desire that my hermitage be erected in this place,” the Lady from Heaven instructed the Amerindian, Juan Diego. Standing on a mountain sacred to the Nahuatl people, the Lady continued, “In it I will show and give to all people all my love, my compassion, my help, and my protection, because I am your merciful mother and the mother of all the nations that live on this earth who would love me, who would speak with me, who would search for me, and who would place their confidence in me. There I will hear their laments and remedy and cure all their miseries, misfortunes, and sorrows.

“And for this merciful wish of mine to be realized, go there to the palace of the bishop of Mexico, and you will tell him in what way I have sent you as messenger, so that you may make known to him how I very much desire that he build me a home right here, that he may erect my temple on the plain.”

“Am I not here, you mother? Are you not under my shadow and my protection? Am I not your source of life? Are you not in the hollow of my mantle where I cross my arms? Who else do you need?” This written account of the vision of the Lady from Heaven, now known as Our Lady of Guadalupe, is amplified by her image, preserved on the tilma, or apron, of Juan Diego. Employing the symbolic language of the native Nahuatl people, this image serves as a visual catechism lesson explaining the mystery of the Incarnation on American soil and the self-offering of Mary who gives Jesus his human body.

Mary’s olive-hued skin clearly identifies her with the Indians and not with Spanish conquerors. An endearing and popular title for Our Lady of Guadalupe is La Morenita, “the brown beauty.” Her pale red dress is the color of spilled-blood. While the missionaries misunderstood the native sacrifices that were performed to preserve life, the natives could not comprehend the wholesale slaughter of their people perpetrated by the conquistadors. Yet, as the color of the sunrise, pale red also suggests a new beginning.

The Lady from Heaven wears a turquoise mantle. This color, reserved for deities and royalty, signifies the abundant life that results from the creative tensions in the universe. To the natives, the trailing stars of a comet indicated the end of a civilization. Here, the stars on the Lady’s mantle announce the beginning of a new civilization.

Only royalty and representatives of deities were worthy of being carried. An angel carrying La Morenita indicates that she came, not with the Spaniards, but on her own. Since a god supported each epoch, the presence of this heavenly being suggests that Mary is announcing a new era.

Among the divinities worshiped by the natives, the moon is among the greatest and the sun is the principal deity. The Lady from Heaven stands on the moon, but does not crush it. The rays emanating from behind her indicate that she hides the sun but does not extinguish it. She is greater than the greatest of the native gods.

Unlike native divinities, Mary looks directly at people. Her face, reflecting humility and compassion, speaks of maternal protection. The black maternity band around her waist indicates that she is pregnant. Over her navel, the symbolic center of the Nahuatl universe, she wears an Indian cross. She brings the child in her womb to the peoples of the New World. Jesus is the center of the universe and the new presence of God. Her brooch, with a Christian cross design, proclaims that she is at once the bearer and a follower of Christ.

By means of this image, Mary, Our Lady of Guadalupe, continually reminds people, especially the oppressed or disadvantaged, that the Incarnation is an ongoing mystery. For a people whose culture is dismissed, whose language is ignored, and whose experience is misunderstood, God looks, speaks, and acts as one of them.

Source: La Morenita, Evangelizer of the Americas, Virgilio P. Elizondo, Mexican American Cultural Center, 1980, and Guadalupe, Mother of the New Creation, Virgilio P. Elizondo, Orbis Books, 1997.

November 21, 2014

“By their untimely demise, they became one with him who loved us and gave his life for us [Galatians 2:20]. Their deaths were the consequence of a life choice made much earlier and kept perseveringly to the end. They are our inspiration and a source of strength for our vocation and mission. We recall that martyrdom can be one possible outcome for each of us as we look at a life coupled with a daily reparatory oblation of Christ.”

Fr. José Ornelas Carvalho, SCJ, General Superior

Martyrs of the Priests of the Sacred Heart:

Blessed Juan María de la Cruz, SCJ

Executed during the Spanish Civil War on Aug. 23, 1936.

Fr. Franz Loh, SCJ

Died in a Nazi prison camp in Germany in 1941.

Fr. Joseph Stoffels, SCJ

Died in a Nazi gas chamber in Austria on May 25, 1942.

Fr. Nicolas Wampach, SCJ

Died in a Nazi gas chamber in Austria on Aug. 12, 1942.

Fr. Nicolas Capelli, SCJ

Executed in Italy during World War II in 1944.

Fr. Petrus Cobben, SCJ

Fr. Andreas Gebbing, SCJ

Fr. Wilhelmus Hoffmann, SCJ

Fr. Franciscus Hofstad, SCJ

Fr. Theodorus Kappers, SCJ

Fr. Isidorus Mikkers, SCJ

Br. Mattheus Schulte, SCJ

Br. Theodurus van der Werf, SCJ

Fr. Petrus van Eyk, SCJ

Fr. Franciscus van Iersel, SCJ

Fr. Heinrich van Oort, SCJ

Died in a Japanese concentration camp in Indonesia from 1944-1945.

Fr. Kristiaan Muermans, SCJ

Died in a Nazi concentration camp in Germany on Feb. 12, 1945.

Fr. François Musslin, SCJ

Murdered in his mission station in Cameroon on Aug. 30, 1959.

Fr. Laurent Héberlé, SCJ

Br. Valentin Sarron, SCJ

Shot and beheaded at their mission station in Cameroon on Nov. 29, 1959.

Fr. Franciscus ten Bosch, SCJ

Fr. Amour Aubert, SCJ

Fr. Hermanus Bisschop, SCJ

Fr. Gerardus Nieuwkamp, SCJ

Br. Henrik Vanderbeek, SCJ

Fr. Henricus Verberne, SCJ

Br. Martinus Brabers, SCJ

Br. Jozef Paps, SCJ

Fr. Jean Trausch, SCJ

Fr. Joseph Conrad, SCJ

Fr. Henricus van der Vegt, SCJ

Murdered during the Simba Revolution in the Congo on Nov. 25, 1964.

Bishop Joseph Wittebols, SCJ

Fr. Jacques Moreau, SCJ

Fr. Clément Burnotte, SCJ

Br. Jozef Laureys, SCJ

Fr. Jeroom Vandemoere, SCJ

Fr. Karel Bellinckx, SCJ

Fr. Christian Vandael, SCJ

Fr. Leo Janssen, SCJ

Fr. Josephus Tegels, SCJ

Murdered during the Simba Revolution in the Congo on Nov. 26, 1964.

Fr. Henricus Hams, SCJ

Fr. Joannes Slenter, SCJ

Br. Wilhelmus Schouenberg, SCJ

Fr. Joannes de Vries, SCJ

Fr. Petrus van den Biggelaar, SCJ

Fr. Arnoldus Schouenberg, SCJ

Fr. Wilhelmus Vranken, SCJ

Murdered during the Simba Revolution in the Congo on Nov. 27, 1964.

Fr. Aquilino Longo, SCJ

Murdered during the Simba Revolution in the Congo on Nov. 3, 1964.

Fr. Paulo Punt, SCJ

Assassinated by organized crime in Brazil on Dec. 15, 1975.

November 7, 2014

When a large crowd of followers approached, Jesus asked Philip, “Where are we to buy bread for these people to eat?” Philip answered, “Six months wages would not buy enough bread for each of them to get a little.” Andrew added, “There is a boy here who has five barley loaves and two fish. But what are they among so many people?” [John 6:2-9]

The Gospel of John uses the Greek term for “boy” that is a double diminutive—which in English might be rendered, “little tyke.” The affectionate term probably refers to the boy’s youth and symbolic smallness. His insignificance echoes the insignificance of available food for so many.

The Gospel of Luke suggests that three loaves, probably similar to pita bread, were considered a meal for one person [Luke 11:5, 6]. If accurate, the boy carried enough for two meals. Yet, this devout Jewish youngster heard the concern. If Jesus needed food, he would willingly share what he had.

He watched closely as Jesus held the food in his hands and then started to break it apart and share it with the people. The boy wasn’t sure what happened next. He knew that the five barley loaves and two dried fish wouldn’t go very far, but Jesus kept moving to the next person with something in his hands. Family groups shared among themselves what Jesus gave them and strangers willingly shared a portion with each other. Was it the boy’s provisions they were sharing or were others sharing what they themselves had?

Whatever happened—God’s generosity, the generosity of people, or both—the boy facilitated this miracle by believing in Jesus enough to share the little he had. A great need is an opportunity to help; and an opportunity to help is a commission from God. If God works miracles, God does so by way of willing, generous hearts.

The mandala pictured above consists of two hands in the midst of a ring of dried fish and barley breads. The boy’s smaller hand fits into Jesus’ larger hand. The heart in the boy’s hand represents his willing, generous attitude. The background colors of yellow, orange, and red in the three rings represent the divine energy or grace generated by the collaboration between Jesus and the boy, and through which the miracle of multiplication happened.

With a child-like faith, the boy placed what he carried in his hands into Jesus’ hands and discovered that his seeming insignificance—as a little tyke or his meager provisions—was more than adequate. To Andrew’s concern, “But what is this among so many people?” the little boy’s big faith eloquently countered, “The little you have, if you are willing to share, is more than enough.” Benefactors, who willingly share what they have, come in all shapes and sizes.

October 31, 2014

In his imagination, Fr. Dehon pictures Jesus as a small child learning his father’s trade. “The Creator, maker of the world, strains to lift a piece of wood to assist Joseph. Who can describe the thoughts of the young apprentice? How his youthful Heart must have sympathized with the work, the privations, and the sufferings of the laboring classes of all times.

“He who was later to say, “Come to me, all you who labor and are burdened” [Matthew 11:28], must have embraced all the labors of the poor and prepared many graces of patience and courage for them; he must have foreseen and merited all the good work of public and private charity for Christian societies. If only all who are blessed with the good things of this world would meditate on the life of Jesus at Nazareth! If all laborers would only ponder over the work, fatigues, and privations of Jesus the Worker!”

Although at first glance, a seemingly pious flight of fancy, this meditation advances the notion that any form of work, accomplished with love, is a physical expression throughout the day of the act of oblation. In referring to the years prior to Jesus’ public ministry Fr. Dehon writes, “The hidden life of the Sacred Heart is the ordinary life comprising only obscure acts that attract no attention. This life does not allow for exterior acts of extraordinary sanctity. Men err in seeing sanctity only in its outward manifestations. Our Lord gives us a different lesson; it is to perform, in an uncommon manner, the most ordinary actions with perfect love.

“It is in these ordinary actions, disdained and scorned as they sometimes are, that we ought to find our sanctity. The condition of a workman, to which our Lord chose to reduce himself, brought with it mortifications altogether providential.” For Fr. Dehon, the ordinary action of performing an honest day’s labor is an offering of self that quietly expresses holiness. Nonetheless, this action requires an honest day’s pay.

“Providential mortifications,” having nothing to do with accepting the exploitation of workers, are those efforts which benefit workers and maintain their dignity. In attempting to comprehend economic structures, to understand worker’s rights as well as duties, and to organize for a living wage and safe working environments, Fr. Dehon reflected the love expressed in the Heart of Jesus. Contemporary reality demands understanding and responding to the consequences of Free Trade, Multi-national Corporations, and income inequality, and advocating for universal access to affordable health care.

Jesus the Worker promises rest for and assistance to all who are weary from their heavy burdens. Laborers, who advocate a just compensation for their work, express an everyday spirituality of taking Jesus’ yoke upon their shoulders. In this act of oblation, they become co-workers with Jesus, not only in accomplishing well the work of their hands, but also in easing the burdens of those who experience the injustice of prejudice and exploitation.

POSTED October 10, 2014

![Original casein painting by Oscar Howe, Yanktonai Sioux [considered the father of contemporary Native American Art], and executed as a 7’ x 10’ x 6” tapestry in Norwegian tapestry wool by Grete Bodøgaard Heikes.](https://dehoniansusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/Tapestry-St-Joes-334x420.jpg)

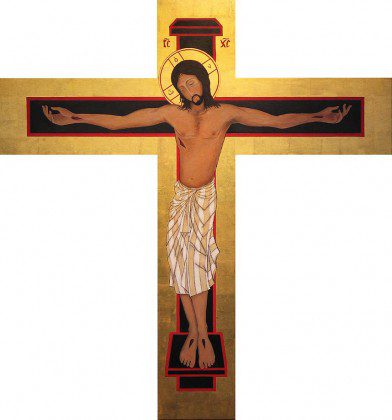

Jesus is clearly presented as a Native American with his tawny skin tone, facial features, and long, straight black hair. A background design in shades of blue seem to swirl about Jesus on the cross, suggesting that the Great Spirit is favorably accepting this offering of self-sacrifice. From a unique vantage point, the cross looks more like a pole, from which Jesus’ body seems to be pulling away.

To Lakota eyes, this image has certain affinities with Wi wanyang wacipi, [“Sun-Gazing Dance”], a sacred Lakota ceremony representing life and rebirth. In this ritual, participants dance around a sacred cottonwood tree. Some men pierce their bodies and by means of pegs inserted into these incisions attach themselves by ropes to the tree. They dance until the skin that holds the pegs breaks, then cut off this loose flesh and make an offering of it at the base of the tree.

The dancers make this individual sacrifice of their bodies for the life and well-being of the community, and to honor Mother Earth and the role of women to give birth. Since the participants have been preparing for this ritual with purification rites, meditation, and perhaps vision quests throughout the previous year, personal transformation is an essential element of the ritual.

While the crucifixion of Jesus and the Sun-Gazing Dance ritual are not the same, the self-offering for the common good underlies both sacred actions. Through the offering of his ministry and his death, Jesus proclaims, “I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly” [John 10:10]. Through the offering of his own flesh and the work of personal transformation, the Sun-Gazing dancer prays, “That my people may live.”

POSTED October 3, 2014

Pastoral ministry is an act of oblation. Fulfilling defined and regular duties, the pastoral minister would have more than enough to make a substantial daily offering of self to God. The human condition, however, assures that those who aspire to serve God’s people are opening themselves to complexity and misinterpretation.

Assessing the needs of a community may reveal an urgency that eclipses what many regard as spiritual concerns. It is ineffective to preach God’s love to someone who is hungry, oppressed, or labelled a sinner. Yet, some believers regard it as insufficient for a minister to witness God’s love by feeding the hungry, advocating for social reform, or showing understanding and compassion.

In his meditation book, The Priestly Heart of Jesus, Fr Dehon writes, “Amazed to find the Savior so accessible to all, and somewhat scandalized by his goodness, the Pharisees said to the apostles, Why does your teacher eat with tax collectors and sinners? But Jesus, hearing it, said, Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick. Go and learn what this means, ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice.’ For I have come to call not the righteous but sinners [Matthew 9:10-13].

“Among these tax collectors was St. Matthew whom our Lord called to the apostolate. He was sitting in the customs house when Jesus, passing, said, ‘Follow Me!’ And Matthew made him a great feast in his house; and there was a large crowd of tax collectors and others sitting at the table with them [Luke 5:29]. Jesus’ kindness to sinners filled them with joy and confidence. It encouraged them to make generous resolutions. Among these tax collectors, indeed one of their chief men, was Zacchaeus, notorious for his unjust business methods, but later on famous for his lavish restitutions [cf. Luke 19:1-10].”

The religious leaders of the day misinterpreted Jesus’ successful ministry because he did not “stay in the sacristy,” to use the description of an attitude that Fr. Dehon tried to refute. The only way for a pastoral minster to understand accurately the needs of people and find ways to address their needs is to be present among them. A human relationship of concern and care is a prerequisite for attending to an individual’s relationship with God.

The minister who embraces his/her sacred task in a less than perfect world, and needs to defend a pastoral practice of presence to those whom one would expect to be supportive, is daily making a pleasing offering to God.

POSTED September 12, 2014

Society does not tolerate a prophetic individual who exposes the failures of its traditional system. Those in power will attempt to squelch the call for reform and to disarm or dismiss the revolutionary element. At first they will try to undermine the prophet’s appeal by dismissing him as a fool or an idealist.

All three synoptic gospels narrate how, at the onset of Jesus’ prophetic vocation, people of his own hometown rejected him. “Isn’t he the son of the village carpenter?” they protested. “Where does he get all those weird notions?” they protested, and drove him out of town. Even his own family tried to restrain him when people said, “He is out of his mind” [Mark 3:21]. Again, in all three synoptic gospels religious leaders accuse him of working in cahoots with Beelzebub, ruler of demons.

When Jesus’ call for reform appeared to gather momentum, the powers in Jerusalem decided on legitimate execution, apologizing for their final solution by invoking the sacred right of the community to use violence to protect itself. “It is better for one man to die than to have the whole nation destroyed” [John 11:50].

Jesus was aware of the inevitability of his execution, so painfully similar to the annual ritual of sacred violence heaped upon a scapegoat, when even beating and taunting was part of the cleansing rite and therefore acts of piety. The naked body shaking with muscle spasms, thirst, and fever became the ultimate embodiment of redemptive atonement, but comprehended only in hindsight. “Was it not necessary for the Messiah to suffer these things and then enter his glory?” [Luke 24:26].

Even our own age has had its bloody rituals of atonement. Moments before his death, Oscar Romero, Archbishop of San Salvador, expressed his own martyrdom in these words: “This holy Mass, this Eucharist is clearly an act of faith. This body broken and blood shed for human beings encouraged us to give our body and blood up to suffering and pain, as Christ did—not for self, but to bring justice and peace to our people.”

Homily, March 24, 1980, Herman Falke, SCJ

POSTED August 29, 2014

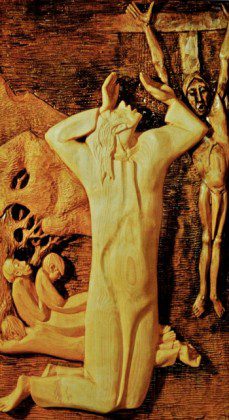

Identifying people of prayer has less to do with watching them pray than with noticing how they live their lives. The Gospel of Luke delights in telling us that Jesus prayed often [after his baptism (3:21); withdrawing from the crowds to a deserted place (5:16); spending the night on the mountain (6:12); praying alone with his disciples near (9:18, 11:1) and with Peter, James, and John on the mountain (9:28-29)]. But Luke shows Jesus praying only on the Mount of Olives [22:39-46]. In the carved image to the right, we glimpse simultaneously Jesus at prayer and how his prayer informed his living.

Although lifting one’s hands was a traditional gesture for prayer, the stretch of his neck as far back as it could go, and his mouth and eyes wide open suggest the intensity of Jesus’ prayer. The specter of crucifixion—hanging on the cross by those same praying hands, his mouth gasping for air, and his eyes blurred in the delirium of pain—is clearly the content of Jesus’ prayer. Behind him, disciples nod off to sleep, their bodies relaxed and indifferent.

At least since Jesus’ 40 days in the desert, the struggle to remain faithful must have consumed his prayer time. Impelled by love to make his Father known, Jesus met with only a modicum of success. Misunderstanding, maliciousness, and the overwhelming crush of need seemed to mock his wisdom, his gentleness, and his inclusivity. The haunting question, “What difference does it make?” blasted in his ears as Jesus prayed on the night before he was executed.

Jesus’ prayer of oblation to his Father, “Not my will, but yours be done,” could never hope to answer satisfactorily the question of significance. It did, however, reconfirm a lifetime relationship of love, trust, and integrity. For those who work for social justice, this image of Jesus at prayer offers encouragement in the face of seeming futility. Most likely, people will never be privy to an activist’s prayer, but they will notice a loving approach to life that is willing to show up, speak up, and let go of the consequences.

POSTED August 8, 2014

Death is the great unknown. No one knows the time or manner of his/her death. Yet, for a faith-filled individual who has spent a lifetime making a daily offering of him/herself, death can serve as the final act of oblation. This is not necessarily a matter of words, but the culmination of an attitude of trusting love nurtured over the years.

In the final moments before his death, Jesus cries out in a loud voice, “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit” [Luke 23:46]. This invocation comes from Psalm 31, a confident prayer that God’s power will prevail over every effort to thwart goodness. The adversaries in the Psalm need not be restricted to external enemies. For most people, internal adversaries include the nagging questions regarding the significance of their accomplishments and the temptation to focus exclusively on their mistakes and failures.

Nevertheless, the grace of a happy death allows an individual to cling to firm convictions based on lifetime efforts. “I tried my best to accomplish what God called me to do. Daily, I have placed myself into God’s hands and now in these final moments, I place my entire life into God’s hands. No doubt, I stand in need of forgiveness; surely, I anticipate the full flow of divine love. Further than this, I cannot see; but this is more than sufficient. Into your hands, O God, I commend my spirit.”

Or, as Fr. Dehon expressed his final act of oblation, while pointing to an image of the Heart of Jesus, “For him I lived, for him I die. He is my everything, my life, my death, and my eternity.”

POSTED July 25, 2014

One day in the Jerusalem Temple, Jesus watched people putting money into the treasury. More than likely, he heard people putting money into the treasury. While we use collection baskets, the Temple had trumpet-shaped chests. Large coins and a large number of coins thrown simultaneously into the chest would make an impressive sound. Two small coins could only whisper.

A widow’s meager offering went unnoticed because it was the amount of noise and the individual who caused the noise that caught people’s attention. Yet, Jesus suggests another criterion for judging generosity. Calling together his disciples, he taught them, “Truly I tell you, this poor widow has put in more than all those who are contributing to the treasury. For all of them have contributed out of their abundance; but she out of her poverty has put in everything she had, all she had to live on” [Mark 12:43-44].

Since Jesus had just critiqued the religious leaders who like to be in the limelight, who spend a long time in prayer just for show, and who “devour widow’s houses,” some Scripture scholars suggest that Jesus was not praising the woman, but deploring the destructiveness of corrupt religion. But Jesus’ teaching focuses on the woman, not the religious system.

The value of her contribution is enormous, Jesus suggests, indeed exceeding the sum of all donations that day. It is not the amount of the donation, but the motivation behind the giving. What impelled this woman of little means to give out of her poverty—indeed all she had to live on? For anyone who has ever been in love, the answer is simple.

To express her love for God, she desired to give what she had. If she worried about her livelihood, she would not be able to express her love. Looking in from the outside, we might say she was foolish because we know that God can read the heart and would not demand such a sacrifice. We are, of course, correct.

But people in love do foolish things—like spending their last two pennies on someone they love. They give it away lovingly because that’s what life is for. Individuals like this widow are the happiest, most fulfilled, and peaceful people in the world—and in Jesus’ mind, the most generous.

POSTED July, 2014

For anyone who wishes to follow the spirit of Fr. Leo John Dehon, the daily act of oblation is valuable only if the prayer leads to some constructive movement, whether another moment of interior conversion or a contribution to the transformation of society. In this light, a daily prayer of oblation can motivate us, in the words of Dehon, to “be good citizens, devoted to our country and to all its interests, moral and material.”

In their Rule of Life, the Priests of the Sacred Heart profess, “We know that today’s world is in the throes of an intense struggle for liberation—liberation from all that does injury to the dignity of people and threatens the realization of their most profound aspirations of truth, justice, love, and freedom. We share these aspirations of our contemporaries, as the possible opening to the coming of a more humane world, even should they include the rise of failure and degradation” [#36-37].

As daunting as this task appears, good citizens can do at least three things: find their voice, cast their vote, and choose to volunteer. In today’s social media, everyone has the opportunity to express an opinion, yet this is often an emotional response parading as incontrovertible truth. While feelings are instructive, it is just as important to discern what is feeding gut reactions. Finding one’s voice in a complicated world demands being informed, about not only the situation at hand, but also its convoluted history and likely future consequences.

Joining a public protest is not for everyone, but talking with neighbors, contacting a representative, and casting votes is within reasonable reach for most people. And since actions speak louder than words, volunteering time and talent helps to bring about the change that a person deems necessary.

“Though entangled in sin,” the Priests of the Sacred Heart admit in their Rule of Life, “we participate in redemptive grace. We want to be in union with Christ, present in the life of the world, through the service of our various tasks” [#22]. Thus, a prayer of oblation, more than a heartfelt recitation of words, is really an overture to daily activity. “In solidarity with Christ, and with all of humanity and creation, we want to offer ourselves to the Father, as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to Him” [#22].

POSTED June 27, 2014

If you sincerely desire to love God with your whole heart, begin by giving yourself entirely to him, in order that he may make of you and perform in you everything that will please him.

To give oneself in this manner to God means complete renunciation of self in order to place oneself in his hands. It is the desire no longer to belong to oneself, no longer to dispose of oneself, but to abandon oneself completely to divine grace in order to follow its every movement. It is the wish to abandon oneself to divine Providence in order to conform to all its dispositions; it is the wish to abandon oneself to the will of God, that it may accomplish in us its divine good pleasure.

Such a gift is a great act of love. Of yourself, you are incapable of it and need a special gift to really produce it. God does not refuse it to whoever truly desires it and sincerely asks for it. Few persons, however pious, possess this real and efficacious desire. They wish to give themselves and still hold back something of their gift; to belong to God and still be their own masters; to follow grace, yet at the same time not renounce entirely their own nature. Nevertheless, without having made this complete gift of oneself, full, entire, irrevocable, we can enjoy the exercise of love at only short intervals and without that continuity which a complete life of love makes of the Christian life.

Your principal daily resolution should be to renew this oblation before as many actions as possible. The practical way of renewing this oblation can be limited to a simple and rapid offering made from the heart. Above all one should not feel so constrained by this resolution as to keep his spirit tense with effort all day long. One must be simple with our Lord. Such strain would quickly fatigue one and lead one to abandon this excellent practice. In working for our Lord everything should be done as simply and as candidly as possible. It is even wise to follow a certain gradual progression to succeed in contracting, effortlessly and painlessly, the habit of a life of oblation.

One should ask himself the following questions: “Have I been faithful in offering to the Heart of Jesus the actions which I had promised to him as a mark of my love? Have I been careful to perform my duties to the best of my abilities in order to give him by such sustained attention a token of my love?”

One should not be troubled by one’s imperfections, but should be faithful in asking pardon of the Sacred Heart each time negligences are perceived. One thus acquires the habit of renewing the offering of every action of the day. At the same time one is careful to perform these actions as perfectly as possible. To do this, renew the morning offering several times a day by means of a quick thought, a moment of recollection before principal actions.

Leo John Dehon, excerpts from The Life of Love towards the Sacred Heart of Jesus, 22nd, 23rd, and 24th Meditations

POSTED June 20, 2014

Among the symbolic use of flora and fauna in traditional liturgical decoration, the image of a pelican feeding its chicks can be found on draperies covering the front of an altar and on vestments. In the 16th century, Durham Cathedral, in England, reserved the Blessed Sacrament in a pelican shaped, silver tabernacle suspended over the High Altar. The pelican’s association with the Eucharist relies on a pre-Christian legend that amplified a superficial observation of nature with an active imagination.

In nature, the adult bird scoops fish from the water into its expandable bill and swallows the fish whole. To feed newly hatched chicks, the adult pelican presses its large pouch against its breast to release regurgitated food directly onto the nest floor. The Dalmatian pelican, the probable source of the legend, sports silvery white plumage with an orange-red pouch hanging beneath a pale yellow, orange-tipped bill.

To the casual observer, the adult pelican was striking its breast, and the orange-red pouch and orange-tipped bill suggested blood. So the legend relates that in time of famine, the adult pelican will pierce its breast with its bill and feed its chicks with its own blood.

While it is easy to dismiss such leaps of fancy, it would be unfortunate to miss that to which this active imagination points. For all its limitations, human nature quietly displays daily acts of sacrificial self-giving. Parents are particularly attentive to and willingly address the needs of their children. Likewise, volunteers at a homeless shelter, activists for a minimum wage, pro-bono lawyers, and neighborhood organizers, among many other generous persons, share a significant part of themselves with those in need.

For Christians, there is no greater example of life-giving love than the gift of Jesus’s own body and blood in the Eucharist. The legend of the pelican, preserved in liturgical art, serves as a symbolic reminder, not only of Jesus’ total gift of self, but also of his gentle command to remember him by doing likewise.

POSTED June 13, 2014

For Fr. Dehon to relate to the second person of the Blessed Trinity, as “my big brother” may seem inappropriately familiar, but he was trying to hold what he could of this mystery, not in his head but in his heart. Being around a big brother can be fun—he knows more and he does more. Naturally, a younger sibling will follow and imitate him. But Fr. Dehon is mindful of more than carefree adventures.

Sent by the Father, the author and preserver of life, the First-born Word of God became the eldest brother of the human race. Why? Dehon suggests the providential mercy of the Father and the loving obedience of the Son provided a human experience of divine intimacy that would shield people from self-destruction and express unconditional love.

Emulating his big brother, Dehon wanted to be obedient to the will of his Father. Yet, in a world filled with complexity, ambiguity, and great need, how could he confidently discern God’s will? Acknowledging blind spots inherent in his own inclinations, Dehon chose to follow the counsel of the Holy Spirit, whom he considered his divine director and who tangibly works through human spiritual directors.

So it is that every self-offering is a profession of faith in the Blessed Trinity. Every act of oblation seeks to embrace the providential will of the Father, as understood through the discerning counsel of the Holy Spirit, and accomplished with the loving obedience of the Son. For Fr. Dehon, the Trinity is not a mystery to understand, but rather a relationship to enjoy.

POSTED May 30, 2014

Since the beginning of our presence in the Philippines, we chose as our home one of the poorest and least developed islands, the island of Mindanao. Here we live and work. Following the example set by our Founder, Fr. Leo Dehon, the SCJ Philippine Region has been involved in different social projects favoring the poor, the sick and the oppressed. Among the different projects, we give priority to the formation of youth and lay leaders, indigenous people, and to the victims of abuse and social injustice.

We run a boarding house for the Higaonon students, who come from very poor and remote villages. We help them in their high school education. At the moment, there are 40 students whom we provide with shelter, food, and all other school related needs.

In 1996, one of our members started the Kasanag Daughters Foundation. This social program offers sexually abused girls the possibility of an integral healing process for them to find their way back to the mainstream of society. At present, the Kasanag Foundation is a home to around 30 girls, providing them with the professional assistance of psychologists, scholarships, and other needed skills and services. Their age is between 8 and 25 years. All of them go to school: at the college, high school, or elementary level.

The SCJ Philippine Region is open to our other entities in Asia and throughout the congregation. Thus, there are many students from Vietnam and India here for their initial formation and studies, and a few religious from Indonesia and other countries who spend their sabbatical time in Manila. The region is also a place of preparation for missionaries who will go to other areas in Asia. We are glad that we can be helpful to others, especially those who seek advanced study and formation. In this way we fulfill the wishes of our founder, Fr. Leo Dehon, and St. John Paul II, that the Philippines becomes a center and a source of evangelization for Asia.

On May 17, 1989, an international group of eight SCJ priests began ministry in the Philippines. 2014 marks the 25th anniversary of SCJ presence in this country.

POSTED May 16, 2014

Truly I tell you,” Jesus declared in amazement, “in no one in Israel have I found such faith.” He referred to a Gentile military officer who came to faith by way of his experience of authority and obedience. Although Jesus agrees to come with him to cure his paralyzed servant, the centurion is aware that Jesus will become ritually unclean when entering a Gentile’s house. Yet, this officer understands what is essential; Jesus is an authority over evil spirits. “Only speak the word and my servant will be healed. For I also am a man under authority,” the centurion explains, “with soldiers under me; and I say to one, ‘Go,’ and he goes, and to another, ‘Come,’ and he comes, and to my slave, ‘Do this,’ and the slave does it” [Matthew 8:5-13].

Perhaps this military officer appreciated Jesus’ own experience more than most. Powerful in word and deed, Jesus was nonetheless under the authority of his Father, to whom he prayed, “Not my will but yours be done” [Luke 22:42]. Jesus learned obedience through what he suffered [Hebrews 5:8] and “became obedient to the point of death” [Philippians 2:8].

Obedience is an essential quality of oblates of the Heart of Jesus. In the Spiritual Directory,Fr. Dehon writes, “To will only what God wills; to entrust themselves entirely to him without delay, without reserve for time and for eternity; to be ready for everything; to give themselves up and to accept all with love as willed or permitted by God: this is a sacrifice agreeable to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.”

The faith of a Gentile military officer needed no signs to assure him of the healing power of Jesus. Likewise, a person who offers him/herself to the Heart of Jesus, discerns the presence of God in daily circumstances, embraces the challenge of living fully in the present, and believes firmly that God’s will is always directed toward healing and abundant life.

POSTED May 9, 2014

It is the same Spirit who distributes the various gifts and ministries at the service of the people of God. Conscious of that call which has repercussions in our whole life, and concerned about responding to it in faithfulness, we want to be attentive to this action of the Spirit, by helping each person, young or adult, discern his vocation and respond to it, in the midst of a world which still constantly needs to be evangelized. We shall take particular care to awaken and to foster the vocation of those who have received the charism to follow Christ in a special manner.

Called as we are to bring Fr. Dehon’s charism to fruition, we want to participate in this activity of the Spirit. We shall respond to Christ’s exhortation, “Ask the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers for his harvest” (Luke 10:2).

We must be convinced that more than anything else it is the example of our life, the spiritual joy, the firm will to serve God and our brothers and sisters, which still today attract candidates. And so each one of us in his relationships with others, each one of our communities in the milieu in which it fulfills its mission, has a duty to give witness of authentic life.

For a young person, also for an adult, it is most often by deepening human and Christian values, by learning to give oneself to others that, thanks the Spirit, the idea of service in the religious and priestly life may arise. We shall be attentive to this deepening, especially in regard to awareness of others, generosity, authenticity of life, clear and loyal responsibility. We shall promote this deepening as much as we can, by contributing to Christian education in families and in schools. In our various forms of contact with the young and with adults, through all our ministries, we must extend to them the Lord’s invitation, “Come, follow me” (Mark 1:17).

SCJ Rule of Life #86-90

POSTED May 2, 2014

The Feast of St. Joseph the Worker is a relatively recent liturgical observance. Pope Pius XII instituted this feast in 1955 to coincide with International Labor Day on May 1. He intended the feast to highlight the dignity of labor and to inspire the collaboration of workers, employers, and governments to establish and maintain safe working conditions, just wages, and necessary benefits.

Fr. Dehon never experienced the Feast of St. Joseph the Worker, but he did anticipate its focus. In speaking of the role of government, he writes, “Justice is the foundation of social relationships, and its purpose is to insure individual rights. These rights, whose violation is a crime of outrage against humanity, must be protected.” In enumerating “The right to life; the right to a fair remuneration for work; the right not to be crushed by excessive work; the right to the joys of domestic life; the right of the woman and child not to be consumed by murderous work, and finally, the right to freedom of duty and conscience,” he asks, “Who will protect these rights if not the law?”

In summarizing the duties of workers, Fr. Dehon explains, “They owe their employers respectful obedience in occupational relationships and respect for their authority; they must faithfully furnish all of the work to which they have committed themselves through a freely-agreed-to and equitable contract; and their demands must be free of violence and must never take the form of revolt.”

As for employers, Fr. Dehon cites the Fifth Commandment [Thou shall not kill] as “the basis for all of the employer’s duties with respect to working hours, weekly rest, and the work of children, women, and particularly mothers of families. He must provide for the fulfillment of these duties through prudent and just regulations. It is all too obvious that the employer must see to the healthfulness of the workplace and that he must take all precautions to prevent accidents which might endanger the lives or health of the workers.”

From a faith perspective, lawmakers, employers, and workers are to fulfill their individual roles not only to the best of their abilities but also with respect and genuine compassion for each other. In a world of fierce competition that values profit above all else, this challenging expectation will surely involve personal sacrifice. Choosing daily to make the effort to promote the common good exemplifies a life of oblation and makes practical a spirituality of the Heart of Jesus, who is the “source of justice and love.”

POSTED April 25, 2014

The story of St. Joseph’s Indian School during the late 1920s and 1930s is a tale of great poverty and generosity, physical and financial hardships, and a seemingly endless series of disasters, catastrophes, plagues, and devastation of almost biblical proportion. It also preserves a record of the daily practice of oblation, an essential spirit of the Priests of the Sacred Heart.

Conditions at St. Joseph’s Indian School were primitive and Spartan at best, food was meager and simple, and coal for the furnace and hay for the livestock were always in short supply. Periodically the water pump broke down, which required the staff and the older children to carry up buckets of water from the Missouri River. In January 1930, the laundry building burned down. In June, a tornado damaged chimneys and roofs, destroyed barns, and cracked walls.

Then on June 17, 1931, a fire destroyed all the buildings on the property except the barn and the granary. Although the decision to rebuild as soon as possible defied all logic during the days of the Depression, reconstruction began immediately. Understandably, this took a toll on Fr. Henry Hogebach, SCJ, in charge of running the school.

A month after the fire he writes, “I feel awfully tired and nervous. The many worries of the past year, the disastrous fire, all the new problems of rebuilding this school and financing the rebuilt institution seem to get to me. I am glad to have Fr. Speyer with me. His unbounded confidence in divine Providence and in St. Joseph, his never-decreasing good humor, his untiring zeal, and his encouraging words keep me up and doing. He is my right hand man; he is up and doing night and day. It is a riddle to me how he can be so full of pep and always jolly with so little sleep and such an amount of work. To have such a companion and friend is the great consolation of the moment.”

Fr. Joseph Speyer, along with the other SCJ pioneers in America, embodied the spirit of oblation. Working to address the need at hand as lovingly as possible with the means available exemplifies the daily practice of offering oneself to God’s will. “Indeed,” Fr. Joe remarked, “we are not performing extraordinary deeds, just our daily work, but it means a great deal for our unfortunate Indian children: nourishment, a home, and an education to fit them for life. It is the little things that count.”

Reflection based on the historical record presented in SCJs in the USA, the Early Years, Paul J. McGuire, SCJ

POSTED April 18, 2014O

Contemplation of the Heart of Jesus means understanding and appreciating the love that motivated all his activities, and this contemplation will lead to greater conformity to his inner dispositions and attitudes regardless of the external circumstances of one’s life. This is the essence of spirituality and the definition of Christ-likeness.

[In understanding Jesus’ passion, Fr. Dehon] begins by contemplating the exterior elements but he reads them as signs and indicators which point him to the interior drama which is unfolding in the human mind and heart of Christ. From there he discovers that Christ’s human dispositions and attitudes are a window on the heart and mind of God. Imitation of Christ and following in his footsteps is more a matter of union with his interior intentions and motivation than conformity to the exterior aspects of his ordeal. This way of transformation and conversion is open to anyone.One of the most concise expressions of his thought on this matter can be found in the notes he took during his thirty-day retreat [using the Ignatian Exercises] in 1893. His meditation on “The Three Degrees of Humility” reveals his understanding of conformity to the will of God with precision and clarity. He notes that Ignatius characterized the first degree of humility as overcoming one’s own inclinations and humbly submitting to God’s will in all that pertains to mortal sin and our salvation. The second degree consists in being indifferent to a life of wealth or poverty, honor or dishonor, so long as one serves the will of God and avoids all venial sin. The third degree of humility, according to Ignatius, involves imitating Christ perfectly by preferring poverty and insults, rather than being esteemed as wise and prudent, because “Christ was treated in the same way before me.”

Fr. Dehon responded to this by asserting that he considered the second degree of humility as its highest or purest form. “It seems even more perfect to maintain a disposition of complete acceptance of our Lord’s will without any preference on our part. This is the spirit of our beautiful vocation. It is the spirit of our profession of love and immolation, which asks us to make frequent acts of acceptance and conformity to the divine will. Ecce venio is our motto. We ought to have it often on our lips and always in our heart.”

From How Father Dehon Read the Passion of Christ, Paul J. McGuire, SCJ

POSTED April 11, 2014:

With too much to read, too little time to integrate new ideas, the pressure of getting good grades, and dreams of a satisfying future, students often contrast their life to “the real world.” Yet the real world is just as frantic, pressured, and populated with dreams deferred.

Indeed, the distinction between full-time studies and full-time employment is not so great when considered from the perspective of motivation, which directly affects action. Both students and workers can accomplish their tasks with a minimum of effort or with passion, with mediocrity or with excellence. Usually, a student’s motivation sets a pattern for the rest of his or her life.

The daily practice of oblation includes regular discernment of God’s will in each of life’s circumstances and the commitment to follow God’s will wholeheartedly. In the real world of academic pursuits, God desires individuals to be the best students that they can be. This deceptively simple expression of God’s will, however, requires much energy to remain consistently focused. Yet, with no need to compare oneself to other students or to compete with them, life is less frantic, less pressured, and less likely to defer the dream of a satisfying present.

POSTED April 4, 2014:

When a devout, young man, who kept all the commandments, approached Jesus to ask, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” he heard an answer that saddened him. Jesus, looking at him with love, advised that in giving away his many possessions, he would have treasure in heaven. Unwilling to do that, the young man walked away. Listening to this exchange, Peter wondered aloud, “Look, we have left everything and followed you. What then will we have?” Jesus assured him that he would inherit eternal life and receive a hundredfold of everything he left behind. [Cf. Mark 10:17-30]

Echoing this story, the Rite of Religious Profession prays, “Father, all powerful and ever-living God, we do well always and everywhere to give you thanks through Jesus Christ our Lord…(who) consecrated more closely to your service those who leave all things for your sake, and promised that they would find a heavenly treasure.” A blessing for the professed religious highlights the essential attitude accompanying this offering, by praying, “May the Lord enable you to travel in the joy of Christ as you follow along his way.”

The image to the right, designed for a celebration of final profession of vows with the Priests of the Sacred Heart, incorporates a stylized version of a formerly used profession cross along with the sentiment, “I joyfully offer all these things.” As a visual statement of oblation, it reveals the attitude of offering one’s entire self to God’s will. The heart, aflame with love, joyfully endures and eventually overcomes the cross of daily trials, even those of aging. Difficult at times, surely, but a total self-offering that always basks in the loving gaze of Jesus.

POSTED March 21, 2014:

Anyone can be an oblate. It’s simple, really, yet at the same time very challenging. But first, what is an oblate? To the scientific mind, oblate describes the shape of a particular kind of sphere, like planet Earth. Better to ask, who is an oblate? In religious terms, this is a person who offers him- or herself to God by following a spiritual rule of life, usually that of a specific religious community. Indeed, the word oblate comes from the Latin word meaning, “to offer.”

It would be unnecessarily limiting, however, to define an oblate as an associate of a religious community. The foundation of Christian living, in its various forms, is baptism, the sacrament that calls individuals to claim their identity as members of God’s family.

The rituals of baptism—anointing with chrism, dressing in a white garment, and accepting the light of Christ—speak both of dignity and responsibility. United with Christ, a faithful Christian offers her life as a model of graced humanity. United with Christ, a committed Christian offers his life to restore a wounded humanity to its original grace.

Religious living, involving vows or promises, is one specific way, among others, to live out the baptismal commitment. Fr. Leo John Dehon, founder of the Priests of the Sacred Heart, originally named his community of men, “Oblates of the Heart of Jesus,” clearly intending that the members offer their lives as servants of God’s will.

“Our whole vocation,” Fr. Dehon wrote in the Spiritual Directory, “our purpose, our duties, our promises are found in these words: ‘Behold, I come, O God, to do your will’ (translating the Latin text of Hebrews 10:7: Ecce venio, Deus, ut faciam voluntatem tuam) and ‘Behold the handmaid of the Lord, be it done to me according to your word’ (translating the Latin text of Luke 1:38: Ecce ancilla Domini, fiat mihi secundum verbum tuum).”

Throughout his writings, Fr. Dehon often used the Latin phrases Ecce venio, Ecce ancilla, or simply fiat as shorthand for expressing the essential attitude “to serve God humbly, to follow all his inspirations and his will.” Instructing the members of his religious community, he wrote, “In all circumstances, in all happenings for the future and for the present, the Ecce venio suffices, provided it is in the mind and heart at the same time that it is on the lips.”

Anyone who offers him- or herself to God by listening for and living out God’s will, as revealed in the Heart of Jesus, is an oblate in the spirit of Fr. Dehon, who prays,

“May the disposition of my heart be a perpetual fiat and an unshakable peace!” Simple, yet challenging.

POSTED March 14, 2014:

Of the innumerable ways to contemplate God’s infinite love for creation, the Priests of the Sacred Heart gaze upon the wounded body of Jesus on the cross, particularly his pierced side that symbolically opens a pathway to his heart. It is their goal to be totally united to the thoughts and sentiments of the Heart of Jesus so that they might be prophets of God’s love and servants of reconciliation, particularly among people who feel shunned, invisible, or oppressed.

Of the innumerable ways to contemplate God’s infinite love for creation, the Priests of the Sacred Heart gaze upon the wounded body of Jesus on the cross, particularly his pierced side that symbolically opens a pathway to his heart. It is their goal to be totally united to the thoughts and sentiments of the Heart of Jesus so that they might be prophets of God’s love and servants of reconciliation, particularly among people who feel shunned, invisible, or oppressed.

Among the many prayers that the Priests of the Sacred Heart recited in common, before Vatican II mandated the renewal of religious life, they prayed this thanksgiving for the Eucharist every night before retiring:

My loving Jesus,

look how far your boundless love has gone!

Of your own flesh and precious blood

you have prepared for me a divine food

in order to give yourself wholly to me.

What has impelled you to such heights of love?

Surely nothing else than your heart

filled with so great a love.

Adorable heart of my Jesus,

burning furnace of divine love,

take my soul into your most sacred wound,

so that in this school of love

I may learn to make a return of love to God,

who has given me such wonderful proofs of his love.

Amen.

Flesh and blood, heart, furnace, wound, and school—these work as synonyms within this prayer. The body of Jesus, on the cross and ever after, speaks of unconditional love for every human body. His heart is the source of love so powerfully transforming that one might think of the energy captured in a furnace of blazing fire. That which impels Jesus is a love so courageously unafraid to be broken open that his wounded side becomes an inviting doorway into a school of love.

Obviously, if the teacher is someone who loved enough to give his life for the benefit of others, this school of love is no ivory tower. The wounded side of Jesus is a place to learn, but never a place to hide. The homework is always the same: to make a return of love to God. The specifics of this response, however, vary among individuals and over time.

As followers of Fr. Dehon, the Priests of the Sacred Heart and the Dehonian Associates commit themselves to “contemplate the love of Christ in the mysteries of His life and the life of people.” By continually integrating God’s love with human need and ever-changing circumstances, this school of love fosters the necessary discernment regarding how best to offer one’s own flesh and blood, united with the flesh and blood of Jesus, for the abundant life of the world.

May weekly postings on the Dehonian Spirituality page, This School of Love, assist in this life-long learning.